Professional Tips And Practical Strategies For Making Decisions About Oxygen Measurement Accuracy

Outline

– Fundamentals: what “accuracy” really means for oxygen and the main sources of error.

– Technologies: electrochemical, optical, paramagnetic, and zirconia—strengths, limits, and where each shines.

– Calibration, sampling, and traceability: techniques that tighten uncertainty.

– Decision frameworks: risk, total cost of ownership, and compliance considerations.

– Conclusion and emerging trends: actionable next steps you can adopt now.

Introduction

Oxygen measurement underpins critical choices—from dosing aeration in water treatment to validating medical gas lines and optimizing combustion. Yet the road from sensor tip to trustworthy number is full of detours: temperature swings, pressure shifts, fouled membranes, and even the way you move the sample. This article translates the science into practical moves you can use at the bench, in the plant, or in the field.

Accuracy Basics: What You’re Really Measuring and Why It Drifts

Accuracy is not a single number; it is the sum of specification, environment, method, and maintenance. For oxygen, accuracy is typically stated as a percentage of reading or full scale, and it depends on the measurement domain. In water, dissolved oxygen varies with temperature, barometric pressure, and salinity; in gases, oxygen partial pressure shifts with altitude, humidity, and flow. That’s why the same instrument can perform differently on a humid summer afternoon than in a climate-controlled lab.

Discover expert insights and recommendations for professional tips practical by grounding your decisions in a few fundamentals. First, define the range you truly need. If you only work between 6–10 mg/L DO, a sensor with narrow, high-resolution coverage in that band can outperform a wide-range instrument. Second, identify the dominant uncertainty contributors. Common culprits include temperature compensation (a 1 °C error in DO can shift readings by roughly 2–3%), barometric pressure variation, and membrane fouling that slows response and biases equilibrium. Third, look at stability over time. Drift rates for modern optical DO probes can be low (often within 1–2% per year), while some electrochemical cells may show more frequent drift tied to electrolyte depletion.

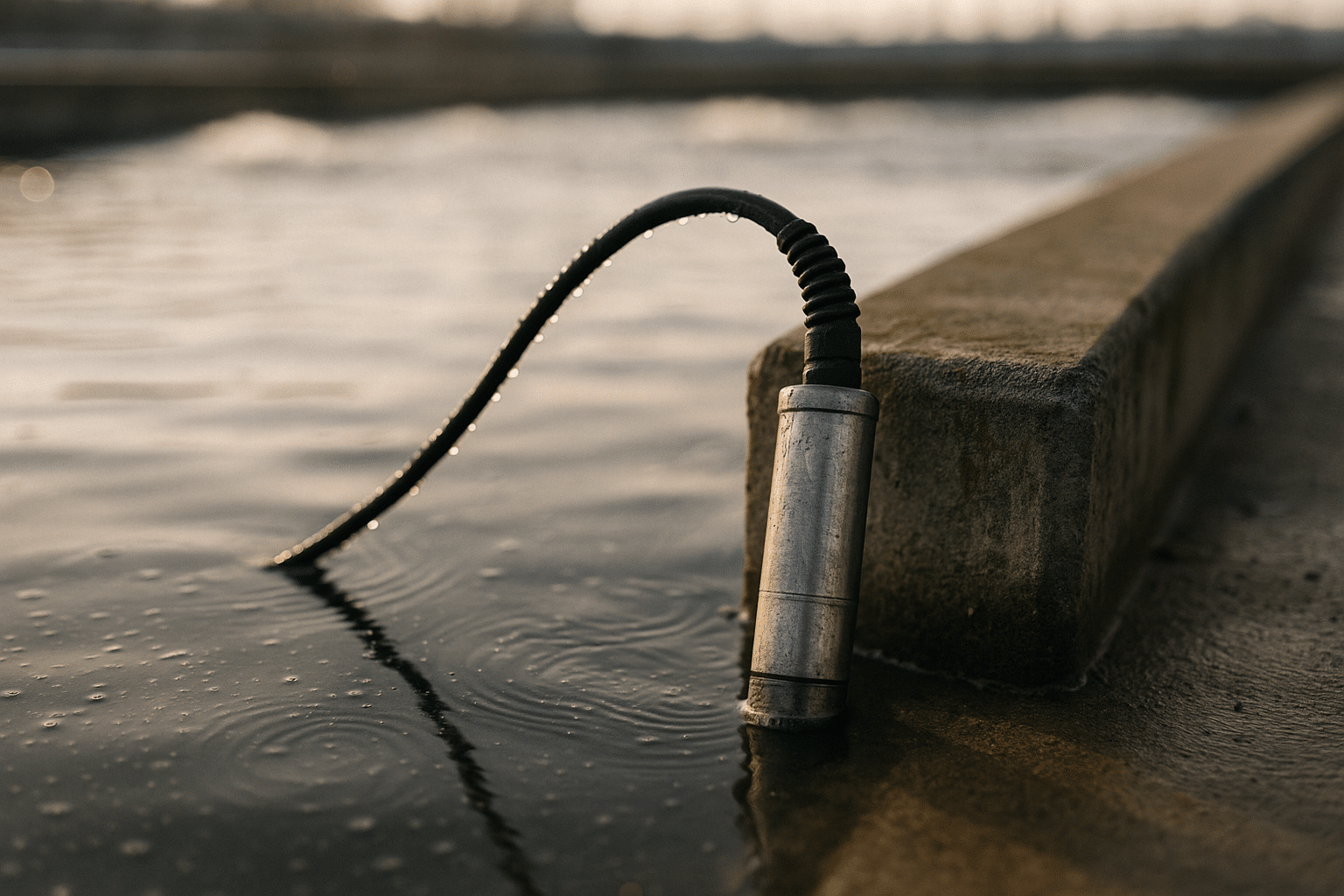

Consider the sample itself. Are you measuring in situ or ex situ? In-line gas measurements benefit from steady flow and conditioned sample lines that avoid condensation; water measurements improve with adequate flow across the sensor tip to avoid boundary layer effects. Small, practical habits often deliver outsized gains:

– Log temperature, pressure, and salinity alongside DO to contextualize trends.

– Use a consistent equilibration time to reduce variability between operators.

– Protect the sensor from bubbles, which can falsely elevate readings in both gas and liquid measurements.

Finally, verify with a secondary reference method when possible (e.g., Winkler titration for DO). Triangulation turns an instrument reading into a defensible result you can present with confidence.

Choosing the Right Technology: Electrochemical, Optical, Paramagnetic, or Zirconia

No single oxygen technology wins in every scenario; rather, each has a niche. Electrochemical sensors (galvanic or polarographic) generate current proportional to oxygen reduction, offering solid performance and fast response, especially in aqueous samples. They do consume oxygen and may require membrane and electrolyte maintenance. Optical (luminescence quenching) sensors measure changes in dye fluorescence caused by oxygen. They generally provide low drift, minimal flow dependence, and do not consume oxygen, making them attractive for long deployments and low-maintenance operations.

In gases, paramagnetic sensors exploit oxygen’s magnetic susceptibility to deliver stable, precise readings across a range of concentrations, with typical accuracies on the order of ±0.1–0.2% O₂ in many applications. Zirconia (solid electrolyte) sensors excel at high temperatures and low-oxygen environments, such as combustion control in flue gas, where robustness and speed matter more than trace-level sensitivity. Key considerations and factors when evaluating professional tips practical options include your operating environment, required range and resolution, maintenance capacity, and the presence of cross-interferents like CO₂, H₂S, or volatile organics.

A brief comparison to anchor decisions:

– Electrochemical: responsive and cost-effective for DO; watch for membrane fouling and electrolyte changes; typical accuracy around ±2% of reading with proper calibration.

– Optical: low drift, limited maintenance, good for long-term deployment; accuracy commonly within ±1% of reading; less flow sensitivity.

– Paramagnetic: excellent for continuous gas monitoring and control; strong linearity; sensitive to flow and vibration if not well mounted.

– Zirconia: rugged at high temperatures; ideal for combustion; needs adequate oxygen at the reference side and care with soot/particulates.

Practical tip: match sensor dynamics to process dynamics. If your process changes rapidly, prioritize response time (t₉₀). If the process is steady, prioritize drift and maintenance overhead. Also, consider how easily each technology integrates with your data infrastructure: analog outputs are simple; digital protocols unlock diagnostics that help you catch problems early.

Calibration, Sampling, and Traceability: Tightening the Uncertainty Budget

Even a great sensor underperforms with a weak calibration. Calibrations should reflect the conditions you actually face: temperature, pressure, and the matrix. For DO, two common approaches are air-saturation calibration (simple, fast) and a two-point calibration (zero with oxygen-free water or nitrogen, then span in air-saturated water). For gas-phase oxygen, a two-point calibration with certified reference gases establishes linearity and exposes any offset. Record environmental conditions during calibration; a small pressure mismatch can imprint a systematic error across your day’s work.

Professional tips and proven strategies for making decisions about professional tips practical often hinge on sampling discipline. Use short, clean, and inert sample lines to minimize lag and adsorption. Ensure flow is stable and bubbles are purged before logging data. If measuring trace oxygen, validate your purge and leak integrity with a pressure decay or tracer test. In liquids, maintain adequate flow across the sensor surface, or gently stir to defeat boundary layers without entraining bubbles. When feasible, compare instrument readings against a primary reference (e.g., Winkler titration) to estimate bias, then incorporate that bias into your uncertainty statement.

For traceability, maintain a chain for gases (certificate numbers, lot, expiry, uncertainty) and for liquids (standard preparation notes, thermometer calibration). Schedule calibration based on risk rather than habit: a low-drift optical sensor in stable conditions may justify wider intervals, while an electrochemical sensor in a harsh matrix may need tighter cycles. To quantify measurement system capability, consider a Gage R&R study. If operator-to-operator variation dominates, invest in procedure clarity and training before buying new hardware. A pragmatic checklist helps:

– Define the largest acceptable total error for your use case (e.g., ±0.2 mg/L DO).

– Break down contributors: sensor spec, calibration gas uncertainty, temperature probe accuracy, and sampling repeatability.

– Address the biggest contributor first; often, that’s sampling or temperature, not the sensor itself.

Decision Frameworks: Balancing Risk, Cost, Compliance, and Fit-for-Purpose

Good choices align technical capability with business reality. Start with risk: what is the consequence of a wrong oxygen number? In medical gas validation, stakes are high; you may require redundant sensing and stringent calibration traceability. In wastewater aeration, the risk is energy waste or process instability; accuracy matters, but reliability and maintainability might matter more. Translate those stakes into measurable requirements: accuracy, resolution, response time, and uptime. Then, map options against total cost of ownership (TCO): purchase price, spare parts, calibration gases or solutions, labor for maintenance, and downtime.

How to evaluate and compare different professional tips practical opportunities becomes clearer with a structured scoring matrix. Assign weights to criteria like accuracy in your operating range, drift, warm-up time, environmental tolerance, diagnostics, and data connectivity. Score candidate technologies or models, and include “integration friction” as a criterion—how easily can you mount the probe, protect it from fouling, and hook it into your historian? For regulated environments, verify conformance with relevant standards and documentation requirements. In harsh industrial settings, ask about ingress protection, temperature range, and exposure to chemicals or particulates.

Make uncertainty visible to stakeholders by expressing measurements with confidence intervals, not just single numbers. When teams see the range, they make safer process decisions. Encapsulate decisions in a short operations playbook:

– Selection rules: when to choose optical vs electrochemical vs paramagnetic vs zirconia.

– Calibration cadence tied to drift, environment, and risk.

– Alarm strategy based on process impact, not arbitrary thresholds.

– Data governance: who reviews trends, how often, and what triggers maintenance.

Finally, pilot before you standardize. A short, well-documented trial in your real environment often reveals hidden costs or performance surprises. Use those findings to refine your scoring matrix and to build consensus across operations, quality, and EHS teams.

Conclusion and Emerging Trends: Turning Accuracy Into Decisions You Trust

Oxygen measurement is evolving, and staying current protects your decisions from becoming stale. Latest trends and essential information about professional tips practical include the rise of digital sensors with onboard diagnostics that flag fouling, drift, or abnormal response profiles. Edge connectivity and wireless gateways are making continuous monitoring feasible in locations that once relied on periodic manual checks. Advanced temperature compensation and salinity-aware algorithms reduce user burden in aquatic environments. In combustion control, higher-temperature zirconia assemblies with protective coatings extend uptime in particulate-laden flue gas.

What does this mean for your day-to-day? Smarter sensors can warn you before accuracy slides, letting you schedule maintenance rather than react to failures. Data historians and analytics can correlate oxygen trends with load, temperature, or chemical dosing to uncover process improvements. Yet fundamentals still rule: sample handling, calibration discipline, and clear procedures will outrun any single feature. If you hear claims of “calibration-free forever,” temper enthusiasm with a plan to verify performance at defined intervals and to keep a simple reference method on hand.

Here’s a compact action plan to close the loop:

– Document your required range, environment, and risk tolerance; translate them into specifications.

– Shortlist technologies aligned to those specs, and run a scored pilot against real process conditions.

– Build a calibration and verification schedule that reflects drift history and regulatory needs.

– Instrument your process for context (temperature, pressure, salinity, flow) so you can interpret oxygen meaningfully.

– Establish a routine for reviewing diagnostics and trends, with clear triggers for intervention.

In short, treat oxygen accuracy as a system, not a single device. If you do, today’s readings become tomorrow’s reliable decisions—whether that’s safeguarding a patient line, tightening a fermentation profile, or trimming energy from aeration without sacrificing performance.